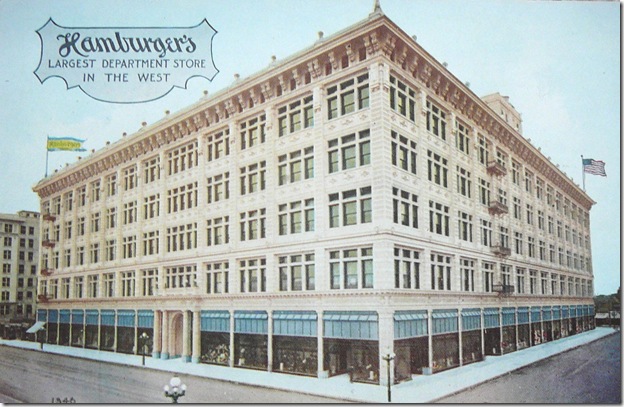

A postcard of Hamburger’s Department Store is listed on EBay as Buy It Now for $2.99.

The classy, oversize May Co. Department Store located at 801 S. Broadway in downtown Los Angeles is up for sale. Today, the mostly empty Broadway Trade Center hosts makeshift swap meet stalls on the first floor in this once celebrated building, the largest department store west of the Mississippi River. Once known as Hamburger’s Department Store, the facility later operated as the May Co. Original owner Hamburger’s was a more elegant and upscale Wal-Mart, hosting every type of business under its roof, even a movie theater.

Hamburger’s Department Store ranked as one of Los Angeles’ premier shopping centers in the early 1900s. Asher Hamburger and his son David immigrated to Los Angeles from Sacramento in 1881, establishing the 20 x 100 foot People’s Store at Main Street and Requena. This department store featured mass but quality goods at fair prices, popular with penny-pinching consumers.

Also by Mary Mallory

Keye Luke

Auction of Souls

Busch Gardens and Hogan’s Aristocratic Dreams

Also on the Daily Mirror

On Location, the May Co.

Movieland Mystery Photo – Architecture Edition

The downtown May Co. is used as a filming location for “The Public Enemy.”

By the early 1900s, customers overflowed the small store. The family decided to construct a bigger and better store, one at a more central location, to attract even more business. Buying land at Broadway and Hill Street between 8th and 9th Streets, the Hamburgers hired architect Alfred Rosenheim to design an elegant, six-story structure in the Beaux Arts Classical style, featuring a white-glazed terra cotta exterior.

Following the Oct. 17, 1905, groundbreaking and almost three-year construction, the beautiful, $4-million Hamburger’s Department Store opened with grand fanfare on Aug. 9, 1908, hosting more than 75,000 people who walked through its almost 13 acres and 400,000 square feet of retail space that day. With a staff of more than 2,300 people, Hamburger’s featured 800 square feet of window frontage, with a 128-foot arch spanning the main doorway on Broadway. Its cross aisle stretched almost a block, 32 feet wide between columns.

Like today’s Wal-Mart and Target department stores, Hamburger’s operated as a giant shopping hub catering to the public’s needs. The store contained its own post office, Wells Fargo office, own fire department, emergency hospital with doctor and nurse, steamship and train ticket booth, express and telegraph offices, bookstore, candy department, drugstore, barber shop, hairdresser and beauty shop, notary public, conservatory, dentist, opticon, cafe, cafeteria, roof garden, photography department, furniture department, piano department, playground, nursery, grocery store, bakery, meat market, fruit market, 80-foot soda water fountain, wheelchair rental service, interpreters, and its own legitimate/moving picture theater, named the Arrow Theater. It also housed the downtown Los Angeles Public Library on its third floor.

As the Oct. 4, 1907, Los Angeles Times reported, a 100 x 80-foot “wee playhouse” would be installed on its fifth floor. “The principal feature of amusement will doubtless be the adventurous form of the moving picture entertainment.” The small theater seating 500 people would feature a small orchestra and stage, and be dark Sundays and nights. Somewhere along the way, the theater acquired the name Arrow Theater, and besides motion pictures, hosted vaudeville acts, meetings, convention presentations, lectures and the like. The department store also provided occasional free children’s programs “with clean entertainment.”

The Arrow Theater featured an hour program of five reels, costing the regular rate of 5 cents, 10 cents for reserved seats. Early ads mentioned it as a “good place to rest when you are tired of shopping,” as it was “comfortable and well-ventilated.” By Aug. 29, 1909, store ads in the Los Angeles Herald mentioned that the theater was open nights and offering “a large and varied program, consisting of motography, art pictures and vaudeville numbers….”

Mostly educational and newsworthy items were shown in the first years, with footage of President Taft presented in October, 1909, 2,000 feet of motion pictures showing the Rheims Aviation Contest in December 1909, film of Theodore Roosevelt returning to the United States from an African Safari in 1909, along with singing of “The Stars and Stripes and You,” and footage of England’s King Edward’s funeral in June 1910.

The May Co. appears in “Employees’ Entrance.”

By 1912, Hamburger’s prominently mentioned in ads that programs changed Mondays and Thursdays, with the Arrow featuring “first run, never shown in Los Angeles” films. The March 8, 1912, program consisted of a couple of songs from a singer, followed by Edison’s “The Nurse,” American Film Manufacturing Co.’s “The Best Man Wins,” starring J. Warren Kerrigan and Marshall Neilan, and IMP’s “The Power of Conscience,” starring King Baggot.

Ads over the next several years prominently mentioned the films of prominent production companies like Thanhouser, Gaumont, Reliance, Keystone, Solax, Kalem, Edison, Essanay, and Selig, and stars like John Bunny, Ford Sterling, Mary Pickford, Kathlyn Williams, Mary Fuller, Irving Cummings, and Alice Joyce.

In April 1912, the Arrow moved beyond just showing programs to the public. The April 23, 1912, Los Angeles Times, reported that the City Council approved leasing the Arrow Theatre for $75 a month for the work of the city’s Board of Censors.

The Arrow also presented other types of programming like lectures, meetings and children’s shows, besides its regular screenings of movies. Music groups like the Bachmann Orchestra performed popular music of the time, Herman the Magician appeared on May 23, 1914, Jewish groups presented talks about the situation in Palestine, and various doctor and dentist conventions featured keynote speeches in the theater.

On Feb. 22, 1909, Professor Edward Bull Clapp gave an illustrated lecture on painting, employing lantern slides. Professor Edgar L. Hewitt, director of the School of American Archeology, spoke Sept. 21, 1909, about the cliff dwellings of Paye Mesa, also using lantern slides. George Washington James lectured on “The Romance of California,” the week of May 18, 1913, accompanied by “a collection of several hundred stereopticon views and photographs.”

The Los Angeles Times catered to zealous baseball fans in fall 1913, hiring the Arrow Theater and other venues around the city to host Free Bulletins of the World Series, where play-by-play descriptions of each game were read aloud to eager attendees.

By 1914, the Arrow shifted its focus to special programming for a more discerning crowd. On Jan. 4, 1915, the theater presented the five-reel All-Star and Alco Films motion picture, “The Old Curiosity Shop.” A few weeks later, it presented the Italian film, “Manon Lescaut,” starring Lina Cavalieri. “Dorothy and the Scarecrow” played the week of Feb. 20. In April, D. W. Griffith’s “Judith of Bethulia” was such a hit that the theater extended its run.

By December 1915, the Arrow seemed to turn its focus back to lectures, with a telephone demonstration Dec. 22 through 24. Pacific Telephone and Telegraph moved the transcontinental phone line from the Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco to Los Angeles for three days, with Supt. George Peck giving a lecture about its use. Thomas A. Watson, Alexander Graham Bell’s assistant, then appeared in a new Edison “talking motion picture” on the development of the telephone, showing the construction of the line between the coasts. Attendees employed receivers placed on each seat to hear American Telephone and Telegraph executive C. E. Willner “read out of the New York evening papers, play operatic selections on a phonograph, and wish everybody in Los Angeles a merry Christmas.”

Soon after, Hamburger’s drastically decreased mentions of the theater in its ads, seeming to focus more on lectures and meetings than screenings of films or live performances. By 1919, the Arrow Theater ended operations.

In 1923, the Hamburgers sold the department store to the May Co., and for the next seven decades, the building operated as the Los Angeles’ flagship for the May Co. After the company abandoned the building around 1990, it sat empty for years before becoming the Broadway Trade Center.

Hopefully, new owners will recognize the unique elements and history of the elegant building, freshening and restoring its hidden glories, and open the theater and other special departments to new legions of consumers.